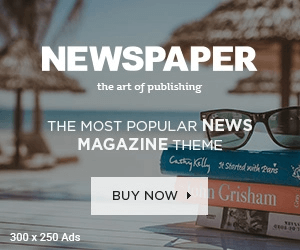

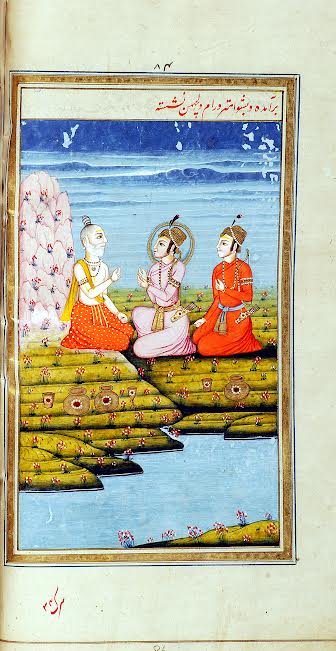

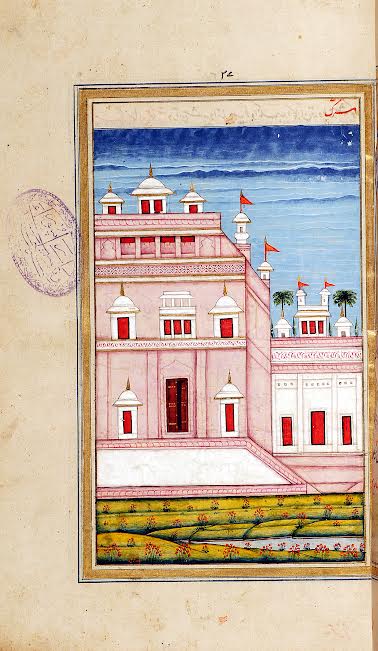

An exquisitely illustrated manuscript of the Rāmāyana by Ādī Kavī Mahārishī Bālmikī [Vālmikī] is preserved within the prestigious Rampur Raza Library in Rampur. This manuscript spans 682 pages and features the Persian translation of the first four kānḍs of the Rāmāyana, meticulously scribed in the elegant Nastʿalīq style of Persian calligraphy. Additionally, the manuscript is adorned with 261 intricately detailed miniature paintings, each vividly depicting various events and episodes from the Rāmāyana.

The manuscript commences with an elegant sarlauḥ (embellishment/ornamental motif) followed by a concise prose preface, which includes a few Persian verses, likely penned by the translator himself. The sarlauḥ spanning pages 2-3 is meticulously executed, showcasing gold cloud bands accompanied by notable red and green quatrefoils set against a gold and blue backdrop. Below, nine lines of text are embraced by a lapis border adorned with a reciprocal crenellation pattern. Beyond this, an outer border graces the page with paired golden leaves, forming enlarged crenellations upon a calming blue background, decorated by gold triangles above.Transitioning to pages 4-5, the borders display expansive cartouches and paired gold leaves, with the intervening space artfully imbued with a rich shade of red.[2] Throughout the manuscript, ʿunwāns (titles) are inscribed using vibrant red ink, providing a striking contrast. The manuscript’s remaining content is elegantly scribed in black, meticulously framed by defined golden borders. Importantly, each illustration is accompanied by a descriptive caption penned in red ink, enhancing the visual storytelling.

The preface of the manuscript provides valuable insights into its origin. It is a prose translation of the Rāmāyana from Sanskrit into Persian, attributed to Sumer Chand. The translation was completed in 1128 A.H./1715-16 C.E., a time coinciding with the reign of the Mughal Emperor Farrukh Siyar (1713-1719 C.E.), at the request of the mystic Rāmkishan. The first kānḍ, known as the Bāl Kānḍ, is marked with a colophon indicating that it was copied by a person named Sayyīd Amīr Shāh in 1242 A.H./1826-27 C.E. In this colophon, Sayyīd Amīr Shāh identifies himself as ‘a devoted servant of the court’ (at pages 139 & 350).

Notably, scholars Ms. Barbara Schmitz and Dr. Ziauddin Desai have attempted to identify Sayyīd Amīr Shāh as the same calligrapher who transcribed Firdausī’s Shāhnāma in 1838-39 C.E., and it is possible that he was working in Rāmpūr during this time. Considering the time frame and his designation in the colophon, it could be inferred that Sayyīd Amīr Shāh was employed by Sayyīd Aḥmad ʿAlī Khān, the Nawwāb of Rāmpūr (reign: 1794-1840 C.E.).

Notably, scholars Ms. Barbara Schmitz and Dr. Ziauddin Desai have attempted to identify Sayyīd Amīr Shāh as the same calligrapher who transcribed Firdausī’s Shāhnāma in 1838-39 C.E., and it is possible that he was working in Rāmpūr during this time. Considering the time frame and his designation in the colophon, it could be inferred that Sayyīd Amīr Shāh was employed by Sayyīd Aḥmad ʿAlī Khān, the Nawwāb of Rāmpūr (reign: 1794-1840 C.E.).

It is worth mentioning that the Rampur Raza Library holds the first half of the Rāmāyana, encompassing the initial four kānḍs exclusively. While the manuscript currently lacks a comprehensive colophon, it is plausible that a complete colophon might have originally appeared at the conclusion of the work.[3]

The text commences with the invocation “Bismillāh ir-Raḥmān ir-Raḥīm” (بِسْمِ اللهِ الرَّحْمٰنِ الرَّحِيْمِ), the opening verse of the Holy Qurān. This resonant beginning mirrors the harmonious coexistence of two religious traditions, embodying mutual respect within a tolerant society and honoring the tradition of beginning a written work. This significant gesture underscores the shared reverence between Hindus and Muslims, offering a glimpse into their cohesive cultural fabric.In alignment with this spirit, the translator’s preface follows, opening with verses of praise for God.

In his preface, the translator articulates the presence of three notable versions of the Rāmāyana, yet highlights his choice to translate the rendition of Vālmikī. This selection is rooted in the version’s esteemed status, endorsed by none other than Lord Rāma himself.Moreover, the preface discloses the translation’s date as 1128 Hijrī, corresponding to the year 1715-16 C.E.

The preface continues in flowery prose, highlighting the translator’s proficiency in Persian and translation skills. In the preface, the name of the translator, Sumer Chand, is cryptically revealed in a versified riddle.[4] Yet, nothing is known about the skilled translator of the referenced work, as he provides no indications of his identity within the prologue. Furthermore, he elucidates that the translation of the Rāmāyana has been accomplished from Sanskrit into Persian. He continues by stating that there are three renowned versions of the Rāmāyana, each characterized by its distinct style and significance. However, his choice for translation falls upon Vālmikī’s version, primarily due to its composition during the era of Lord Rāma—a version that was both heard and praised by Lord Rāma himself.Following that, within a rubāʿī (quatrain), he provides further insight, expressing that ‘the Rāmāyana is humanity’s most ancient history, surpassing all recorded chronicles. It unveils hidden values intrinsic to humanity, guaranteeing its recognition throughout the world.’

The preface continues in flowery prose, highlighting the translator’s proficiency in Persian and translation skills. In the preface, the name of the translator, Sumer Chand, is cryptically revealed in a versified riddle.[4] Yet, nothing is known about the skilled translator of the referenced work, as he provides no indications of his identity within the prologue. Furthermore, he elucidates that the translation of the Rāmāyana has been accomplished from Sanskrit into Persian. He continues by stating that there are three renowned versions of the Rāmāyana, each characterized by its distinct style and significance. However, his choice for translation falls upon Vālmikī’s version, primarily due to its composition during the era of Lord Rāma—a version that was both heard and praised by Lord Rāma himself.Following that, within a rubāʿī (quatrain), he provides further insight, expressing that ‘the Rāmāyana is humanity’s most ancient history, surpassing all recorded chronicles. It unveils hidden values intrinsic to humanity, guaranteeing its recognition throughout the world.’

[1]Head, Department of Persian, L. S. College, B. R. Ambedkar Bihar University, Muzaffarpur (Bihar); former Tagore National Scholar, Rampur Raza Library, Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. <kaifyy@gmail.com>

[2]Mughal and Persian Paintings and Illustrated Manuscripts in Rampur Raza Library, p. 97

[3]Mughal and Persian Paintings and Illustrated Manuscripts in Rampur Raza Library, p. 98

[4]which says:

واو و دال و الف و کاف نوشتم ده و چند // نامِ من بود به ترتیب چو کردم پیوند

(means: I wrote vāv (و /व), dāl (د /द), alif (الف / अ) and kāf (ک / क) ten times with Chand (چند / चंद), together when collected it appears to be my name.)

In this verse-riddle, vāv (و /व), dāl (د /द), alif (الف / अ) and kāf (ک / क) are Perso-Arabic alphabets, each carrying a numeral value as per Perso-Arabic alphanumericsystem called Abjad numerals or Ḥisāb al-Jummal.

According to Abjad numerals, vāv (و /व) is equal to 6, the value of dāl (د /द) is 4, alif (الف / अ) is 1 and kāf (ک / क) is 20. Now, according to the hint given in the riddle, multiplying vāv (و /व) with 10 gives 60 (6×10), dāl (د /द) gives 40 (4×10), alif (الف / अ) gives 10 (1×10) and kāf (ک / क) gives 200 (20×10). In the Perso-Arabic alphanumeric system, 60 is the numeral value of sīn(س / स), 40 is the value of mīm (م / म), 10 is the value of yā (ی / य, ऐ) , and 200 is the numeral value of rā (ر / र) that together form Sumer (سُمیر / सुमेर) which by adding Chand (چند / चंद) becomes Sumer Chand (सुमेर चंद), that is the name of the translator/author of this beautiful manuscript.

for Perso-Arabic alphanumeric system or Abjad numerals refer to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abjad_numerals